From the late Middle Ages to Renaissance: A new world view

In the late Middle Ages, art began to turn its attention increasingly to the secular world. Proud portraits of bourgeois citizens are evidence of this development as is the attention attributed to the depiction of nature, as visible in the prints by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528).

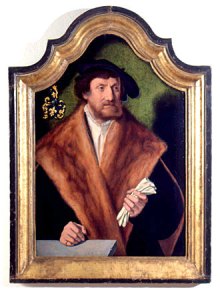

Portrait of Balthasar von Kerpen: The portrait, which was created ca. 1535, is a main work by Barthel Bruyn (1493–1555), Cologne’s leading Renaissance master. The portrayed businessman belongs among the esteemed patricians of the free city. The dapper clothing reveals his status: over a shirt with a finely ruffled collar, he wears a coat whose fur edging falls broadly over the shoulders. In his left hand he holds a pair of white gloves, while his right rests on a stone balustrade. Resplendently pictured next to his head is the illustrious family coat of arms. Barthel Bruyn is revealed as a master at reproducing his models’ facial features, but also in subtly depicting character traits: seriousness and dignity, determination and drive. This eminent painting was included in the St. Gallen collection in 2002 as a donation from the Albert Koechlin Stiftung.

The likeness of the barely twenty-year-old woman who faces us in festive finery has been successfully identified: Selvaggia di Baldo Fieravanti from Florence, who married Medici- Günstling Niccolò Ferrini in 1569. She lived in Quartiere di Santo Spirito, and died in 1583, one year after her husband. Her life-size portrait was probably made for the wedding. As painter, recent research proposes Niccolò di Giovanni Betti (1571–1618), an artist who worked for the Medici-Hof as successor to Agnolo Bronzino. Meticulous description of detail, convincing materiality, and coloristic finesse make the portrait a representative work of Florentine Mannerism. In the Kunstmuseum, it is thus now a paramount representative of the personalized portrait art of the waning Renaissance.

At approximately the same time, ca.1540, the Flemish painter Herri met de Bles (ca. 1510–1555) created the spectacular Way to Calvary. At the center of the symmetrically constructed composition, a bizarre rock covered with trees protrudes from rolling grounds. Embedded in it is the simultaneous depiction, based on medieval models of the departure from Jerusalem, the Stations of the Cross, and the crucifixion. The artist translates Christ’s Passion in a dramatic cloud structure with sharp light-dark contrasts, while the heavenly Jerusalem promises redemption in the background. The Way to Calvary is an emulation of Joachim Patenir, who as the first northern artist, painted so-called overview landscapes. Whereas the depiction of the details in Cavalry is «realistic,» the «world landscape» type appears particularly artificial in its overall appearance, with its mood of a practically imaginary quality.

The Flemish Birth of Christ with Dancing Shepherds is virtually unprecedented. Painted in Antwerp in 1515, the altar-like panel was probably produced on the occasion of a religious festival. The shepherds, dressed in colorful garments, dance a lively round dance and celebrate the birth of Christ. Angels appear from heavenly light and inspire them to hymns of prise. The verses are distributed on banners above the dynamically overflowing painting. A pasture fence protects the holy family in the stall from the loud world. In front are additional shepherds with their sheep, many equipped with three-fingered gloves and the so-called shepherd’s shovel. Two are eating, one plays the bagpipes, while others warm themselves at the fire in the wintery cold. This genre-like, old-Dutch depiction is a rarity of the greatest art- and cultural-historical as well as socio-historical significance—although its creator remains anonymous for the time being, and its precise meaning and function still await investigation.